author: Kevin Curran PhD

updated: 02-18-2023

Will biosimilars for cell and gene therapies be successful?

Short answer: Yes, I think they will.

In time, biosimilars for cell and gene therapies will be approved, marketed and eventually…these biosimilars will eat into market share of the original, branded drug.

There is no insurmountable reason why the biosimilar’s safety and efficacy cannot be comparable to the originator version. In addition, manufacturing cell and gene therapies is gradually becoming routine and economies of scale are starting to lower production costs.

In 2023, we are currently watching antibody biosimilars gain market share from the blockbuster, antibody-based originator drugs. Prescribing physicians need to be convinced of clinical similarity, but once this is established then the hospital and insurance formularies will switch over to the generic versions. Humira has been the most lucrative antibody biosimilar from an annual revenue standpoint (~20B annual sales). In 2023, about 50% of prescribing physicians state they are comfortable with the generic version of Humira.

As cell and gene therapies fall off their patent cliff, the same biosimilar intrusion will occur.

Ok, let’s back it up….

First of all….what are biologics?

Biologics are a class of drugs that require living biological material in their design or manufacture. When people in the life science industry speak about biologic drugs, they are often referring to monoclonal antibodies (Humira, Herceptin, Rituxan, Embrel, Remicade….). These are the blockbuster biologics that have been on the market for decades. However, the category of biologic drugs also includes newer categories of drugs, including: gene therapies, cell therapies, CAR-T, RNA therapies and peptides.

Antibody drugs have truly revolutionized modern medicine. They’re highly versatile. By recombining DNA in various sequences, we can design fusion or modified proteins with optimized functionality. Antibody drugs are highly specific. The variable region of the antibody protein can attach to a very specific epitope region on a drug target. These features are substantial upgrades from the small molecule paradigm.

Unfortunately, biologic drugs also arrived with hefty price tags. Developing and biomanufacturing these large molecule drugs is expensive. That price was passed on to payors.

Biologics often cost up to 200-300K for an annual treatment. However, here’s the good news for payors and for the entire healthcare economy… these drugs will eventually lose exclusivity and experience generic price competition.

In 1984, the Hatch-Waxman act introduced a regulatory process that brings generics to market. Since then, we have seen generics come to market with many small molecule drugs. Drugs like Lipitor Viagra have experienced massive price erosion as the originator company was forced to compete with new generics offering the same drug. In 2020, we are beginning to see this generic process play out with biologic drugs. The regulatory pathway to approve biosimilar competitors was signed into U.S. law in 2010, but healthcare savings have been slow to materialize. Between 2015 and 2020, about 30 generic companies were granted generic approvals for a biologic drug, but many have not actually gone to market with their biosimilar and those that did go to market haven’t generated significant price reductions.

It seems, this is beginning to change. A report by IQVIA illustrates the progress that is happening on the biosimilar front. A handful of biosimilars are now being used alongside the original ‘first to market‘ version. For example, many of Genentech’s blockbuster, biologic drugs (Herceptin, Avastin, Rituxan) are now losing significant market share from biosimilar competition.

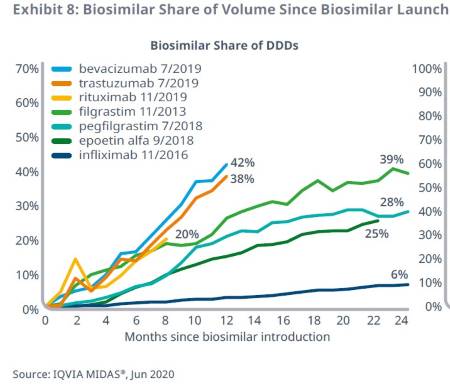

Recent biosimilars have achieved high volume shares, projected to reach more than 50% within the first two years.

IQVIA, 2020

The three most recently-launched biosimilars in 2019 have achieved significant uptake within their first year: bevacizumab (42%), trastuzumab (38%), and rituximab (20%).

These biosimilars are tracking towards more than 50%, or nearly 60%, by the end of two years on the market — substantially higher than prior biosimilars and similar to the high rates of adoption in Europe.

IQVIA, 2020

Hit the subscribe button below to follow Kevin’s newsletter on Substack.

Kevin Curran PhD is the founder of Rising Tide Biology. His newsletter explores exciting new developments in biotech, including: Artificial Intelligence in drug discovery and the use of gene editing to eliminate genetic disorders.

He also examines the traditional market structure of the pharmaceutical industry and provides ideas for alternative models that could enhance global patient access to new medicines.

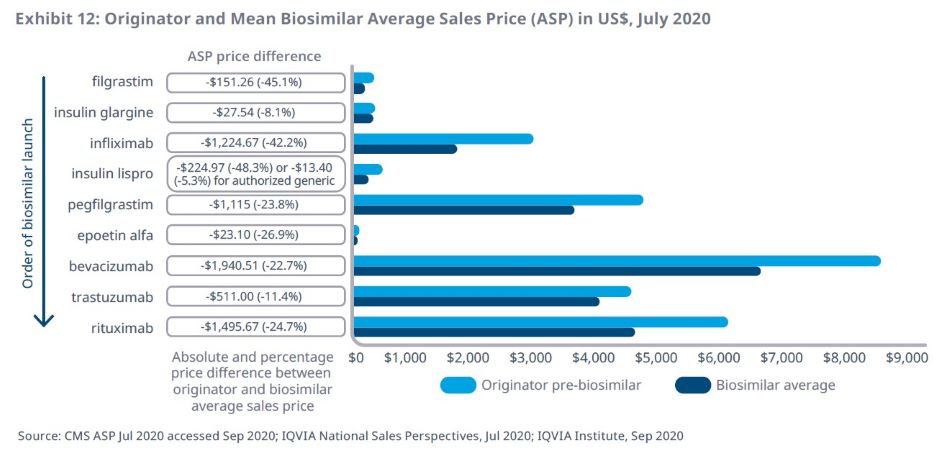

Usually, competition brings about lower prices for payors. In the pharmaceutical industry this rule can not be assumed. That said, we are now seeing 10-40% price reductions. See image below for details.

Absolute savings from biosimilars vary, with larger savings from more recent launches where originators were more costly

The three most recent biosimilars launched in 2019, bevacizumab, trastuzumab, and rituximab, have seen ASP price reductions of $500–$1,900 for a standard course of treatment, potentially a factor in the high uptake of these biosimilars.

IQVIA, 2020

What works for antibody biologics should also work for cell/gene therapy biologics.

It is worth considering how biosimilar competition will play out with FDA approved cell and gene therapies.

Between 2017-2020, we saw a handful of cell and gene therapy approvals. Kymriah and Yescarta are approved in the CAR-T space and Zolgensma received approval as a gene therapy for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Zolgensma arrived with a price tag of 2.1 M and the CAR-T drugs cost approximately 400K each. These are one time payments.

What will happen when these cell and gene therapies fall off their patent cliff and lose market exclusivity?

A drug patent expires after 20 years. Once drugs go to market, they often have 15 years of patent life left. At some point between 2030-2035, we will see the first wave of cell and gene therapies lose market exclusivity. Will biosimilar companies be able to swoop in and recreate these products? Most likely, the answer is yes. I think biosimilars for cell/gene therapies will follow the same path as antibody based biosimilars.

I also think that improvements in manufacturing will mean we will see a dramatic price erosion when cell and gene therapy biosimilars arrive on the market.

Below, I’ve assembled a few reasons why biosimilars for cell and gene therapies will be successful.

- IND enabled cell therapies (CAR-T) are already available in some hospitals. In house CAR-T manufacturing provides a roadmap for generics to create biosimilars. These hospitals use similar genetic constructs as approved constructs. They spend years developing manufacturing and clinical protocols before offering IND enabled cell therapies to patients for a ten fold reduction in price.

- Gene therapy manufacturing will become more affordable as more manufacturing organizations come online. We are currently experiencing a massive bottleneck in gene therapy manufacturing capacity. Manufacturing organizations (CMOs) are booked five years in advance. This high demand is incentivizing many vaccine manufacturers and other CMOs to enter in the viral vector based gene therapy manufacturing space. In ten years, it seems highly likely this space will see ample manufacturing capacity, at which point manufacturing costs should decrease.

- Economies of scale will continue to lower manufacturing costs. As the gene therapy manufacturing industry matures, companies will naturally evolve efficiencies to further reduce operating costs.

What if natural monopolies develop within the cell and gene therapy space?

Complex biologics do pose additional challenges to genericization. Any genetic alteration to cells in the human body are permanent. This raises the bar of concern for regulatory agencies, such as the FDA. At some point in the 2030s, the FDA will be considering a biosimilar zolgensma. They will need to see consistent manufacturing as well as safety/efficacy in animal data. Most likely, they will also want to see some human clinical data. For a gene therapy, this may involve a small trial on 5-10 patients. It will be a challenge to enroll patients into a generic zolgensma clinical trial. If the branded and well-tested zolgensma is already on the market, why would a patient want to take on the risk of a new and lightly tested generic version of a permanent gene therapy?

If gene therapy generic companies find they cannot enter the market, then the FDA may need to impose contractual genericization on any cell/gene therapy company that has a natural monopoly on one particular treatment. How would that work?

Once the originator company loses market exclusivity of their drug, this originator company would then be under contract to continue producing the drug at a marginal cost. This marginal cost could be 2x production cost of each therapy. In this sense, the originator company is under contract to produce their own biosimilar once their patent expires. I realize this requirement represents a fundamental change in the way drugs are regulated. We may find that such a dramatic policy change is necessary to accommodate the new modality of cell/gene therapies.

If the idea of contractual genericization is of interest, I recommend reading The Great American Drug Deal by Peter Kolchinsky.

Today is 10/16/2020. I will be updating this page in the future. Many factors will be moving around on the cell/gene therapy biosimilar front in the next decade. I’ll be doing my best to keep up….